For a more detailed review about the medical treatment and management of SCAD please refer to Spontaneous coronary artery dissection – A review. by Yip A., Saw J., in Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2015 Feb;5(1):37-48.

The long-term prognosis for SCAD survivors after their initial SCAD presentation is good. Recurrent SCAD events, however, are frequent and these patients must be followed closely. Conservative medical management for stable patients with resolved ischemia is typical. Revascularization via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) may be necessary for a small percentage of patients.

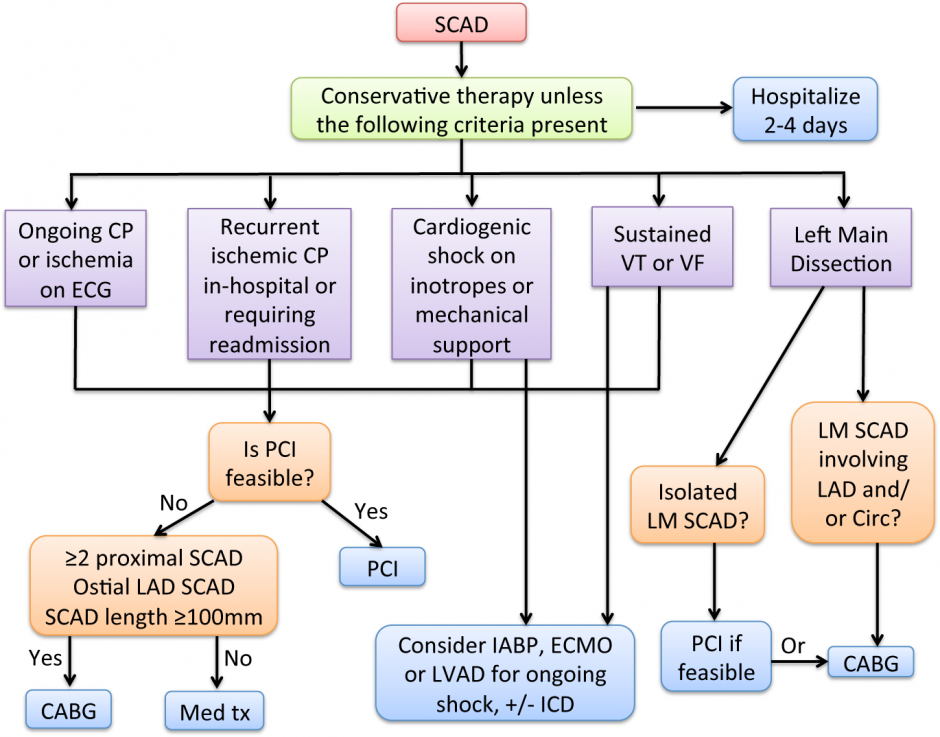

The following figure is a flow-chart providing a process for managing the medical treatment of SCAD patients.

Figure 1: Management algorithm including revascularization for acute presentation of SCAD [1]

SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting

Medical Therapy

Standard acute coronary syndrome (ACS) pharmaceutical agents may or may not be beneficial for SCAD. In addition, the use of antiplatelet therapy in the treatment of SCAD is also unclear for patients not treated with stents.

A percentage of SCAD events involve intimal tears that are prothrombotic and would likely benefit from antiplatelet therapy. Therefore, we typically administer aspirin and clopidogrel for acute SCAD patients and follow-up with clopidogrel for 1 year and aspirin for life.

However, the use of new P2Y12 antagonists (prasugrel and ticagrelor) is unclear and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors for acute SCAD management have also not been evaluated. Due to their greater potency, higher bleeding risk, and potential risk of extending dissections, they are not normally recommended for SCAD treatment.

Anticoagulation treatment for SCAD is controversial. While there is a risk of extending dissections this is balanced by the potential to resolve overlying thrombus and improve true lumen patency. Although ACS patients presenting at hospital are typically treated with heparin agents, it is recommended this be discontinued once SCAD is detected on angiography to avoid extension of intramural hematoma (IMH).

Medical management of SCAD deviates from standard ACS therapy. In particular, thrombolytic therapy should be avoided for patients with SCAD. Therefore, early coronary angiography to establish SCAD is important. If, however, angiography is not available, then thrombolysis should not be withheld for ST-elevation MI patients because the overall frequency of thrombotic occlusion is much higher than SCAD. While there have been anecdotal reports of successful thrombolysis with SCAD, these reports are limited and most data suggest negative effects with thrombolysis for SCAD.

Beta-blockers offer benefits in aortic dissection by reducing arterial wall shear stress. Extrapolating these benefits, we routinely administer beta-blockers for SCAD, both acutely and long-term.

While nitroglycerin may be useful in alleviating ischemic symptoms during acute SCAD presentation, it is not routinely used long-term.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are administered when there is significant post-MI LV dysfunction (ejection fraction ≤40% and class 1 indication).

Statin use for non-atherosclerotic SCAD has not been studied. We would administer statins only to patients with preexisting dyslipidemia.

Revascularization

The choice to revascularize a dissected artery depends on both the affected coronary anatomy and the patient’s clinical status. Conservative treatment is preferred for most stable patients without ongoing pain. However, patients with ongoing chest pain, ischemia, ST elevation, or hemodynamic instability should undergo PCI, especially when the dissection affects major arteries with sizable myocardial jeopardy.

Emergency CABG should be considered for patients where the dissection involves the left main. However, dissections of proximal segments of left anterior descending (LAD), circumflex or right coronary artery should be intervened percutaneously if feasible.

Stenting may not be practical where the dissected artery segment is distal, of small calibre, or when the dissection is extensive. Attempts at revascularization of dissected coronary arteries may be very challenging and can often result in poor outcomes. Initially it may be challenging to advance the coronary guidewire into the distal true lumen. Additionally, the IMH of a dissection may extend antegradely or retrogradely with angioplasty, further impeding arterial blood flow and extending the dissection. Distal coronary arteries with dissections may be too small to implant stents. For dissected arteries that are larger, the dissections may also be longer and require long stents, leading to increased risk of restenosis. Furthermore, IMH resorb and heal over time, and may result in late strut malapposition, increasing the risk of very late stent thrombosis especially after cessation of dual anti-platelet therapy. Lastly, the natural history of the dissected segments is such that the vast majority heals spontaneously, and patients appear to have good long-term outcome if they survive their initial event. We recommend reserving PCI for patients with ongoing chest pain and ischemia when the lesion is amenable to stenting, and to consider CABG for extensive dissections involving the left main.

If PCI is attempted, there are strategies that may improve outcome. If the lesion is relatively focal, we recommend selecting longer stents that would provide adequate coverage for both edges of the lesion (at least 5-10 mm longer proximally and distally). This attempts to accommodate extension of the IMH proximally and distally when compressed by the stent. We recommend OCT or IVUS to ensure adequate stent coverage and wall apposition. For longer lesions, a multistep approach of stenting the distal edge, followed by the proximal edge, and then stenting the middle of the dissection, may be useful in preventing IMH propagation. The use of bioresorbable stents also has theoretical benefits of avoiding late stent malapposition following resorption of IMH.

There is no consensus as to repeat imaging after SCAD, irrespective of revascularization strategies. Because a significant proportion of patients have recurrent chest pains after their initial event, we find it useful to repeat coronary angiography several weeks later to investigate potential ischemic causes of pain, and to assess arterial healing.

References

1. Saw J, Aymong E, Buller CE, Starovoytov A, Ricci D, Robinson S, Vuurmans T, Gao M, Humphries K, Mancini GBJ. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Association with Predisposing Arteriopathies and Precipitating Stressors, and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7(5):645-55.

DISCLAIMER: This webpage presents information regarding what we have learnt from our SCAD cohort.

Our suggested management may or may not apply to individual patients presenting with SCAD.

Patients should contact their health care professionals for specific individual management of their condition.